Earlier, this blog covered the life of George K. Greene (1833-1917) and in the posting it was revealed his association with Albert C. Koch. So here is a blog entry documenting Koch's life and his connection to paleontology and the Louisville area.

Time with George Greene

An article about George K. Greene in The Courier-Journal, Sunday September 17, 1911, entitled "Fossils Found Revert To Age When Louisville Was At the Equator" lists how Greene became associated with Koch. "One day Dr. Koch, an eminent French geologist, stepped at the Greene home. He was collecting geological specimens for a French nobleman, who was to endow a college in his native land. Dr. Koch became interested in the young man at once. Soon the interest was mutual, and when George was 16 years old he left home 'to become a geologist'. For several years he traveled about studying under Dr. Koch, and aiding in his work."

An earlier The Courier-Journal article, on Sunday March 11, 1894 entitled "Curios and Fossils The Unique Life and Work of a Self-Made Scientist" tells another story of his relationship to Koch. "he was just thirteen years old when a peculiar encounter decided his bent in life. To the boy's native town, in an overland trip to collect fossils for a French nobleman, came a foreign scientist-Dr. Koch-traveling with his wife. The lad became fired with an ardor for the wonders opened to him by their pursuit, and journeyed on with them. Three years were spent in this prolonged and delightful geological picnic, rambling nearly all over the United States, gathering fossils and scientific lore. At the close of this jaunt the Kochs settled in Golconda, Ill., and young Greene began on his own account a fossil hunt, which probably only death will terminate."

Learning this, I wanted to find out more about Albert C. Koch so I bought an English translation of his trip taken to the United States in 1844-1846 to collect fossils. It was published in German in 1847 and was translated into English entitled Journey through a Part of the United States of North America in the Years 1844-1846 by Albert C. Koch translated/edited/introduction by Ernst A. Stadler. I found a seller on Amazon that was selling new copies wrapped in plastic from the 1973 publish date for under $10 including shipping. I guess it was not the biggest seller back then and thus there is a large collection of uncirculated books still available as of this writing.

Early Life of Albert Koch

Albert Carl Koch was born on May 10, 1804 in Rielzch, Saxony (now Germany). His father was Johann Eusebius Sigismund Koch (1776-1851), a magistrate there and his mother was Johanna Maria Wilhelmina Sophia Martini (1782-). A natural history cabinet existed in his household containing stuffed birds and shells. No record exists of Albert's early childhood or how he was educated. His brother Louis Leobolt Koch was born October 10, 1806 in Saxony. He emigrated to the United States in 1834 but returned to Europe in 1836 and returned to the U.S. for good in 1854. After a relatively long life, Louis would die January 6, 1883 in Golconda, Illinois.

Albert migrated to the United States at the age of 22 (1826) and it appears he went to St. Louis. In 1830, he married Miss Elizabeth Reid (1810-1875) of Philadelphia [the 1860 census taken in St. Louis list her name as Elisabetha born 1808 in Massachusetts]. They moved to St. Clair, Michigan where his two daughters Rosalia (1831-1899) and Maria (1834-) were born. His son James Albert Koch (1836-1907) was born in St. Louis, Missouri. His oldest two daughters were baptized in St. Louis and the family later left there in 1840 to live in Europe. His youngest child, daughter Georgiana Koch (1843-1927) was born in London, England. She died Georgiana Hobeboom in Stapleton, Nebraska on November 29, 1927.

His Famous Mastodon Find & Charles Lyell

Koch had been hunting for large fossilized animals in the years 1838-1839 around the Missouri area and had found various remains. It was not until 1840 that he recovered an almost intact large vertebrate fossil animal. On March 24, 1840 he had received news of a farmer while building a mill had discovered some large fossil animal bones in Benton County, Missouri. It took him six days to find a way across the rain swollen Osage River and then a 24 mile horse back ride to the Pomme De Terre River. Once across it was another 30 miles to a valley where the fossil was discovered. He spent 4 months there extracting a fossilized mastodon. He then used 3 large wagons with a special constructed oak suspension to protect the fossils. Each wagon was pulled by 4 oxen which made its way to Boonville, Missouri and then by steamboat to St. Louis. By August 1840 he had assembled the Missourium later known as the Missouri Leviathan or Mastodon giganteus.

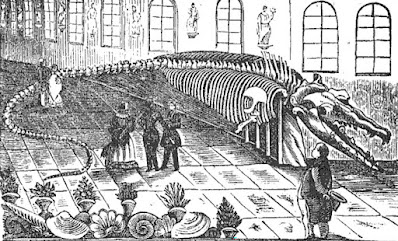

In a October 29, 1841 letter to Dr. Mantell, Charles Lyell (1797-1875) writes about Albert Koch's Missourium fossil find. "I went with Dr. Harlan to see the great skeleton brought by a German, Koch, from the Missouri; a very large Mastodon which he calls the Missourium. He has turned the wonderfully huge tusks the wrong way-- horizontally-- has made the first pair of ribs into clavicles, and has intercalated several spurious dorsal and caudal vertebrae, and has placed the toe-bones wrong, to prove, what he really believes, that it was web-footed. I think he is a mixture of an enthusiast and an imposter, but more of the former, and amusingly ignorant. His mode of advertising is a thousand dollars reward for any one who will prove that the bones of his Missourium are made of wood. He is soon to take them to London, when you will have great treat, and see a larger femur than that of the Iguanodon. Harlan is lost in admiration at the bones of this and other individuals, all belonging to the old Ohio Mastodon of Cuvier, from very young to very old individuals. He has also other fossils"

A somewhat harsh assessment but as you can see in the above picture, the animal is not assembled correctly. In 1847, Albert publishes his observations in an 1844-1846 trip to the United States. In his discussion about collection fossils at Martha's Vineyard, Albert recounts visiting Lyell in London and being shown a walrus head skeleton found at Martha's Vineyard. Lyell told the whole was visible on the slope at the seashore there but no one had extracted it. Lyell had bought the skeleton head from a local man. Koch thought the skeleton to be too white to be fossil. As note on page 21, "But because it was pointed out as a fossil by such a famous geologist. I did not dare contradict him." Koch asked if Professor Richard Owen (1804-1892) had studied the specimen which he had but did not a straight answer as to whether it was a fossil. Koch then wrote, "The whole thing left me very unsatisfied, and I then resolved in secret to investigate more closely if I should ever come to Martha's Vineyard." He tracks down the man who found the skull and he found it sometime in 1840 "on an elevated seashore tow English miles from he local lighthouse." The man found no other parts of the animal. Koch goes to the site and it consists of "postdiluvian formation, namely a mixture of sand and clay with pebbles and large round stones washed ashore." Koch then concluded it was a modern walrus and thus publishing a back at you shot to what Lyell wrote about him and the Missourium fossil.

Fossil Hunting on the American East Coast

Koch visited the man who found the walrus skull again and purchased "two of the largest shark teeth which possibly have ever been found on Gay Head." Koch left the area on August 10, 1844. He notes he collected 585 specimens (58 various vertebrae, 19 bones, 62 shark/saurian teeth, a tooth & incisor of Iguanodon like creature, 3 big saurian incisors, 3 exterior covering of saurian, 8 green sand songlomerate with fish bones/scales, 326 crab or lobster pieces, 38 petrified shells representing 3 species, 40 pieces of cane like fossil plant, 12 crystallized petrified cane specimens, and 20 unknown petrifactions. He left Holmes Hole on August 14, 1844 and sailed to New Haven where he took a train to Boston. In Boston, he met with Dr. Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874) and visited the museum of society of natural history. Koch then delivered a letter from Privy Councillor Ludwig Reichenbach (1793-1879) of Dresden to Mr. Prattford in Cambridge with Mr. Melancour, Mr. Ludewig, and Dr. Richter. While there, they visited the botanical garden and the library at Harvard University.

On August 16, 1844 Koch traveled to New Haven, where he met Professor Benjamin Silliman (1779-1864) on August 17, 1844. They took his packed fossils to the geology lecture room at Yale University. Professor Charles Upham Shepard (1804-1886) of Charleston, South Carolina joined them. They identified the 3 saurian incisors to belong to ancient crocodile. Dr. Silliman commended Koch on his fossil finds. Koch departed for New York August 19, 1844 and arrived the next day. He visited the American Museum there and saw a number of bones excavated from Missouri but badly damaged which identified as "antediluvian elephant or mammoth, and only a few of the Mastodon giganteum."

Koch left the next day by steamship and eventually made his way to Erie, Pennsylvania where he took the canal. He then made it to Cleveland, Ohio by September 1, 1844 and got passage on the Ohio Canal to Portsmouth, Ohio which would get him to the Ohio River. Koch arrived at the Ohio River on September 7, 1844 where he got passage on a steamboat.

Koch's Fossil Collecting in the Louisville Area

Albert visited the Louisville, Kentucky area from September 9 to November 3, 1844. In his published diary of the American trip of 1844-1846, on Saturday, September 7, 1844 Koch writes, "we arrived at two o'clock in the afternoon in the town of Maysville, which lies close on the bank of the Ohio in the state of Kentucky... we used this time to climb the high rocky banks of the river... some scattered stones my attention was drawn to the fact that the local region must be rich in petrifications, and I found my expectations almost surpassed because the mountains were full of beautiful shells, among which I also discovered some coral species." He then collected as many as he could carry and took them back to the steamboat. The next day he visited

President William Henry Harrison's tomb in North Bend, Ohio.

He arrived in Louisville, Kentucky on a Monday and started his quest for local fossils on the morning of September 9, 1844 by visiting

Dr. Asahel Clapp (1792-1862) who told him the best collecting was at the falls located in Jeffersonville, Indiana. Koch wrote about the next day, "My expectations concerning the local fossils I found quite satisfied, if not surpassed. The shells and corals are frequently so beautiful and perfect, as if the animals whom they once served as houses and covering still lived in them." The next day he found more fossils noting they appear to be 45-60 species of corals and that they were loose on the rocks [silica fossils eroded out of limestone matrix]. By Thursday, Koch writes that the heat is almost unbearable and there is no shade on the fossil beds. He is concerned for his health as there is such large numbers of mosquitoes and his glad the beds have netting. "Many of the local inhabitants were laid low by fever, and others wandered around like spirits risen from the grave."

Friday, September 13, 1844 his collection of fossils was large and by his estimates he is lacking specimens from only a few species. On Monday, he met again with Dr. Clapp to review Koch's finds. Dr. Clapp tells him he had found species he had not seen even after collecting for 20 years in the area. The next day he hired a boat to take him to some rocky islands in the river for more collecting and then used the rest of his time to sort and pack specimens. Koch visited Dr. Clapp on Saturday to see his collection and determine which fossils to now look for. During his time in the Louisville area, Albert Koch writes about various political events that he attended related to the presidential election between

James K. Polk (1795-1849) and

Henry Clay (1777-1852).

By September 23, 1844, Koch begins to investigate the Charlestown, Indiana area for fossils on advice of his landlord [Mr. Greene]. He finds a Euomphalus shell of the Teredo family and another shell of a Pleurarynchus. Later in a dry creek bed, he writes he found several small species of sea urchin. On Wednesday, the 25th, he explored another dry creek bed about a mile from the city and found a Pentremites blastoid. By Thursday, he had collected now so many fossils he was only looking for rare specimens to keep. For the rest of the month, he continues to collect fossils and consults on occasion with Dr. Clapp about his finds.

On Sunday, November 3, 1844, he writes "Yesterday afternoon I made a farewell visit along the falls of the Ohio, where I had experienced much quiet pleasure by finding so many beautiful relics of the primeval ocean."

He refers to staying with a "Mr. Green" and his family while in the Louisville area. He also crates the fossils he finds and stores them with a merchant in Jeffersonville, Indiana. Months later in his diary, he writes on Thursday, June 12, 1845 that he arrived in Louisville by steamboat. "We were early enough event to go by steam ferry to Jeffersonville in Indiana, where I had left in storage the objects which I had collected last fall at the Ohio falls. I found them in good condition and had them brought to Louisville." The next day he took a mail packet to Cincinnati and from there boarded the steamboat Financier to Pittsburgh.

I believe his landlord while staying in Indiana was

Captain George Greene (1802-1877) who was a merchant in Jeffersonville and the father of George K. Greene. Young George was definitely influenced by all the fossils being collected by Koch and it set him on a life long path of collecting the fossils of the Falls. The son would have been 11 at the time and Greene says when he was 16 he joined up with Koch to collect fossils and was with him for 3 years. If that recollection was correct he probably was with him from 1850-1853

Fossils from Keokuk, Iowa Territory

After leaving the Louisville area and traveling by steamboat to St. Louis, he learned about fossils being found in the "bituminous coal formations" in the Iowa Territory. While traveling in the area he records, "I found here a rich yield of beautiful petrified shells which were new to me, and also two new species of coral."

Finding the Hydrarchos

Koch arrived on March 15, 1845 in Washington County, Alabama which he writes, "I set foot with almost indescribable feelings. The place which contained the Hydrarchos discovered by me lies near a not unimportant river, the Sintabouge River. Surrounded by woodlands, it is an elevation of volcanic origin on which where is no wood. The larger part of the surface consisted of a yellowish limestone mass, covered in part by black-brown earth which contained, particularly in the limestone, many beautiful fossils."

He does not list how many workers helped him extract the fossil. The creature was in a "sort of half-circle". The head was turned around and the lower jaw with most of its teeth was about foot away from the rest of the skull. The spinal processes were mostly destroyed and the ribs were extracted and supported by custom made iron arcs. Koch talks of making a side trip to Clark County, Mississippi to investigate another large skeleton but only found a ruined laid out dorsal vertebrate.

By April 20, 1845 he shipped off the "Hydrarchos" fossil by land and proceeded to John G. Creagh's plantation at Tattilaba Creek, Clark County, Alabama. On April 28, 1845 he started extracting the fossil head of the Zygodon. Koch later sent the fossils unearthed in Alabama to the port of Mobile on the sailing ship Newark bound for New York. The ship sunk off Key West, Florida in a violent storm. As luck would have it for Albert Koch, the salvagers sent "the giant sea serpent free of all charges... since this fossil sea monster was a scientific object and they were well aware that the discovery of it had entailed much difficulty and expense for its finder."

Hunting for Zeuglodons in Alabama

In January of 1848, Koch was looking for more vertebrate fossils in Alabama. On February 7, 1848 his crew unearthed a

Zeuglodon fossil that took several months to extract and then ship to Dresden, Germany. It took craftspeople 8 months to expose the 96 foot fossil and it was put on display May 6, 1849 at the Royal Academy of Dresden. It then moved Breslau and then Vienna for a year (1850-1851). Next the fossil was displayed in Prague and then sent back to the United States. In 1853, it was exhibited in New Orleans at the Great Southern Museum. Koch then moved it to St. Louis where he sold it to Edward Wyman of the St. Louis Museum who in turn sold in 1863 to the

Col. Wood's Museum of Chicago.

Death

Albert died of "lingering torpor of the liver" on December 28, 1867 at his brother Louis Koch home in Golconda, Illinois. He was buried on the estate but his body later moved to the IOOF Cemetery (aka Odd Fellows Cemetery). The inscription on his tomb stone reads "Hydrae Arcana Aprumque Immania Condita Terra Titanum Exegit Duae Monumenta Manent" which translates to "immense things buried in the earth, which now survive as monuments."

Legacy

It appears that an image of Albert Koch is painted into a

large vignette that 7.5 feet high and 348 feet long that is stored at the City Art Museum of Saint Louis. It was painted by John J. Egan in 1850 and it shows workers unearthing a vertebrate fossil while Albert Koch explains the area Dr. Montroville Wilson Dickeson (1810-1876).

|

Mammut americanum mastodon fossil recovered by Albert Koch in 1840 and sold to British Museum of Natural History in 1844 where it is still on display. Photo by Don Hitchcock in 2018 at donsmaps.com

|

The mastodon fossils that Koch uncovered, displayed in a traveling museum and then sold to the British Museum of Natural History, still exist. The main mastodon is on display in Hintze Hall at the

British Museum of Natural History. The area in Kimmswick, St. Louis County, Illinois where the fossil was uncovered is now the

Mastodon State Historic Site. Interestingly, Koch's work inspired another entrepreneur Charles William Beehler (1844-1914) to found Humboldt Exploration Company in 1898 to prospect for fossils at the Kimmswick Bone Bed site.

The whale fossil he sold to the Berlin museum was destroyed in 1945 as Germany bombed during World War II. Some things did survive the war, a few of the mastodon bone fossils and stone artifacts are still at the museum. As historian Ilja Nieuwland discovered some pieces of Koch's original

Hydrarchos at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin and documented on his appropriately named

Hydrarchos web site. He lists those parts as "several vertebrae, some teeth, fragments of both jaws, part of a

humerus, one posterior skull section, and casts of various skull parts." Ilja also found Koch specimens at Teyler’s Museum in Haarlem, The Netherlands that sold to them in the early 1850s consisting of vertebrae and a skull missing its mandible.

The other Alabama whale fossil that was sold to Wood's Museum of Chicago was destroyed during

Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Koch excavation of whale fossils were recognized by scientists of his day. Ludwig Reichenbach named a species after him in 1847

Basilosaurus kochii (Reichenbach, 1847) now known as

Zygorhiza kochii (Reichenbach, 1847).

He is now used as an example in geology text books as a fossil hoaxer (e.g. The Changing Earth: Exploring Geology and Evolution by James S. Moore & Reed Wicander, 2014 page 175). If one does a search for "Albert Koch fossils", numerous posts can be found that reference him and his mis-interpretations of the mastodon & whale fossils he found.

This

2020 YouTube video by John Ruthven shows that even after all these years Albert Koch's fossil contributions are still being discussed.

My Observations

It is a mystery as to where all the Louisville area fossils Albert Koch collected in the fall of 1844 ended up. Maybe in some museums in Europe or possibly they were destroyed or misplaced during the wars that followed in the 20th century. More research is needed but I believe he returned to Louisville in the early 1850s and collected more coral fossils.

On George Greene's recollection of Albert Koch, it mystifies me on how in two different Courier Journal newspaper interviews he thinks that Albert Koch is French and not German. Also what his age is when he encounters Mr. Koch though it appears Koch visited Louisville numerous times during his lifetime. Another point is to how well each of them knew each other as neither named fossils after the other. What regard did Koch have on Greene in the type of paleontologist became, he definitely influenced him on economic value of fossils and in their trade.

From reading Albert Koch's account of American travel in 1844-1846, a better understanding of the health aspects of living in the area at this time: the large quantities of mosquitoes and the spread of disease that caused debilitating fever, food safety and the spread of gut ailments, steamboat boiler explosions, sailing ships lost at sea in storms, the reliance of water levels and ice accumulation in preventing river travel, and the being at the mercy of the wind and storms in ocean sail travel.

Albert Koch has an interesting place in American paleontology. His fossil excavations of large vertebrate were impressive in the presence of primitive transportation and the rural areas in which they were found. After reading his travel account, it is obvious he lacks scientific training but his talent in personal communications, logistics and observation are how he finds and moves fossils from the field to the general and scientific communities.

UPDATE January 2024:

After writing this posting I found a newspaper article entitled "A Mighty Fossil Hunter: Sketch of a Hoosier Scientist, Prof. George K. Greene" by Emma Carleton of New Albany, Indiana in the The Indianapolis Journal, Sunday, November 28, 1897 page 10. It as yet another version of Greene's connection to Albert Koch. "When young Greene was thirteen years old, having had but about ten months' schooling in that time, there came to his native town a German geologist, Dr. Koch, traveling the country over, with his wife, a French woman, on an interesting geological pilgrimage, making an extensive collection of fossils for a wealthy French nobleman who was endowing a Parisian university. Mrs. Koch was an expert geologist, but she weighed two hundred pounds, and was in much need of a small boy to accompany her and carry her bag of fossil specimens and tools. For this office the little Kentucky boy was offered and accepted; and until he was nineteen year old he lived this unusual and interesting life, traveling with this scientific man and woman from fossil field to fossil field all over the country, by foot, carriage, rail or steamboat, as their route determined. Of these peregrinations in the cause of science Prof. Greene has many pleasant reminiscent stories to tell. New Harmony, at that time, being the intellectual Mecca of the West, thither he often accompanied the Kochs, there meeting the eminent Robert Dale Owen, David Dale Owen, Richard Owen and many other scientific men who were attracted to that remote Posey county stronghold of learning. From these advantages came naturally the knowledge and enthusiasm which gave to his life its scientific bent. The lead mines of Golconda, Ill., it may be mentioned, where discovered by Dr. Koch during one of his scientific forays, and, after a final trip to France, he settled in Golconda, expecting to become wealthy; this dream was not realized, however, and he lived and died there without having made a fortune."

UPDATE June 2024

The Courier-Journal article from Sunday morning September 17,1911 (Section 4, page 1) entitled "Fossils Found Revert To Age When Louisville Was At the Equator" by Dan Walsh Jr. The following is the section about George K. Greene and Albert Koch.

"This interesting old man was born at Columbus, Ind., seventy-six year ago. He is the son of George Graham Greene, a farmer and merchant of Hancock County, Kentucky. His mother was on a visit to the Indiana town when he first saw the light of day. His early education was received in the public schools, but he studied Latin and science under private teachers. One day Dr. Koch, an eminent French geologist, stopped at the Greene home. He was collecting geological specimens for a French nobleman, who was to endow a college in his native land. Dr. Koch became interested in the young man at once. Soon the interest was mutual, and when George was 16 years old he left home "to become a geologist."

For several years he traveled about studying under Dr. Koch, and aiding in his work. His whole interest was soon in geology, and in 1870 he moved to Jeffersonville so that he might be near the falls of the Ohio, which he declares to be the finest fossil bed in the world. As his studies progressed he moved about over Indiana, and finally, in 1878, he settled permanently in New Albany."

Some Publications by Albert Koch

"Remains of the Mastodon in Missouri," American Journal of Science 37, 1839, pp. 191-192.

A Short Description of Fossil Remains, found in the State of Missouri by the author. 8 pages, 1 plate. St. Louis: Albert C. Koch, publisher, Churchill & Stewart, printers, 1840.

Description of the Missourium, or Missouri Leviathan; together with its supposed habits, Indian traditions concerning the location from whence it was exhumed; also, comparisons of the Whale, Crocodile, and Missourium with the Leviathan, as described in the 41st chapter of the Book of Job, 2nd ed., enl. 20 pages. Louisville, Kentucky: Prentice & Weissinger, printers, 1841.

"Description of the Missouri Leviathan, together with its supposed habits, and Indian Traditions concerning the location from whence it was exhumed." The Farmers' Cabinet, and American Herd-Book 6 August 1841-July 1842. Philadelphia: Kimber & Sharpless, 1842.

Sources

Journey through a Part of the United States of North America in the Years 1844-1846 by Albert C. Koch translated/edited/introduction by Ernst A. Stadler, Southern Illinois University Press, 1972, pp. 177.

“Albert Koch’s Hydrarchos Craze: Credibility, Identity, and Authenticity in 19th Century Natural History,”

Science Museums in Transition: Cultures of Display in Nineteenth-Century Britain and America, by Carin Berkowitz and Bernard Lightman (eds.), University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017, pp. 139-161.

LINK

Meeting Hydrarchos in Person(s) by Ilja Nieuwland, April 5, 2015

web site link

Side Note

Ernst Anton Stadler was born November 10, 1928 in Passau, Bavaria, Germany and died at the age of 83 on March 26, 2012 in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. While living in Munich, he was employed by Radio Free Europe from 1950 to 1954. He met American

Frances Cordell Hurd (1917-2000) in 1953 while she was working with the Red Cross in Germany. They married in 1954 and moved to St. Louis. Ernst worked for the brewery Anheuser-Busch. His in-laws were Carlos F. and Katherine Hurd who were aboard the S.S. Carpathia on April 14, 1912. They interviewed a number of survivors picked up from the S.S. Titantic sinking. He became famous as the

first reporter to get a first hand accounts of the sinking which was published in Pulitzer papers Post-Dispatch and New York World.